David Olivant

David Olivant was born in 1958 and grew up in Watford, a non-descript town on the northwest edge of London. He was awarded a BA in Art from the Falmouth School of Art in England in 1980 after which he studied for three years at the Royal College of Art in London where he received an MA in Painting in 1984. Following graduation, he was awarded a Commonwealth Scholarship to work in India. He lived in New Delhi for three years in the late 1980’s. After a brief return to England and a short residence in Stockholm, he moved to Chicago.

Following his first solo exhibition in Art Heritage Gallery, New Delhi, Olivant had a solo show at the Center for International Contemporary Art in NYC, just a stone’s throw from MOMA. He was favorably full-page reviewed by Kay Larsson in New York Magazine which led to his ultimately being represented by Stephen Solovy in Chicago. Olivant has periodically contributed reviews to Art Critical, Art Ltd and Square Cylinder. His first teaching position was at Southwest Texas State University after which he accepted a post at California State University of Stanislaus in 1995, where he taught for 25 years before retiring in 2020 and moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico. He is now an artist member of Amos Eno Gallery in Brooklyn, NY.

Mark Van Proyen in a recent catalog essay on David Olivants’s recent work states:-

“Because these works entail various forms of pictorial representation, there is no forthright declaration of the authority of the object-as-object, but there is always a subtle restaging of the dialectical tension between objecthood and its hypercoded opposite, with human outcomes that are provisional and far from certain. The unusual materiality of Olivant’s new Retroglyphs supports this assertion…

It slowly dawns on the viewer that the what of these works and the how they are made both mirror and editorialize on each other, all the while bearing witness to the consequences of a social world on the verge of amusing itself to death, struggling to fully apprehend the consequences of its translation of myopia into zeitgeist…

Olivant’s figures are pictured as being free to come and go, but they do neither, because wherever they might travel to and from would offer little that was significantly different from the possibilities available in the locations in which they are depicted. They live in a Sartrean hell of programmatic indifference, impassively seeking salvation from a runaway complexity that changes guises while moving in rhetorical circles. Nonetheless, it is their hell, and the fact that it is portrayed as a familiar one makes it seem something like home. In that way, these protagonists are tragicomic, earmarked by a canny balancing of the elements of charm, pathos and absurdity to slyly suggest the ways that each of those aspects is an obliquely mirrored reflection of the others, all stage-managing anxious relations between multiple modes of disconnected particularity.”

The artist recognizes aspects of himself in this eloquent analysis and in addition senses that although, as Van Proyen states, the figures neither come nor go, despite being free to do either, what they vainly, perhaps stupidly, seek, having digested their dog-eared copies of Mikhail Bakhtin, revisited early encounters with the Master of St Petersburg and aped the doomed anti-heroes of Andrei Tarkovsky, is a form, no matter how vexed or fleeting, of primary contact with themselves, each other or the viewer. This is their ultimate search and one from which they scarcely cease despite its inherent futility, perhaps because what is searched for is the very thing that is doing the seeking.

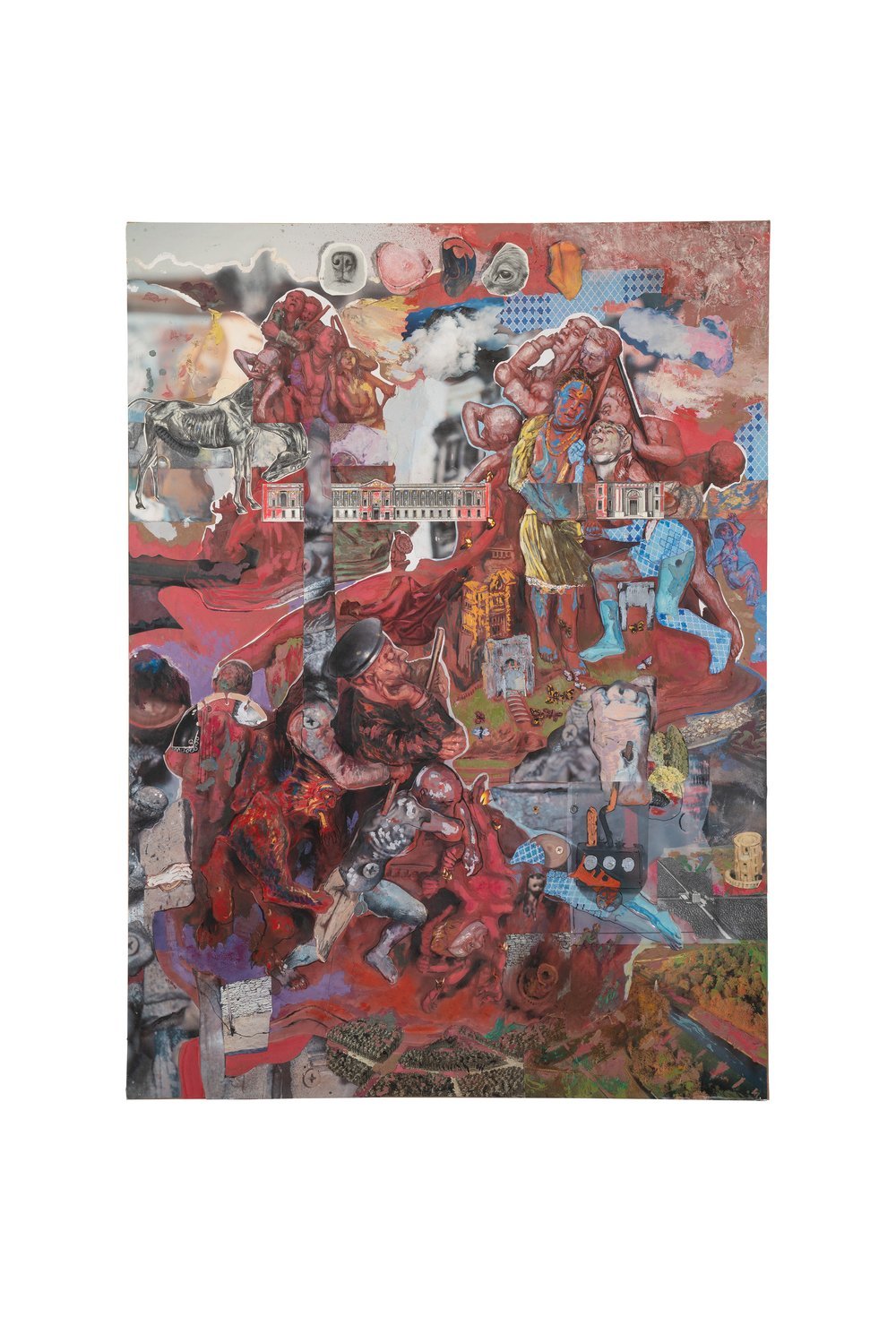

Backside Pilgrimage, 44" x 30", 2023

Four Spoon Father, 30" x 44", 2023

Gaps in Transmission, 41" x 30", 2022

Gravity's Denial, 30" x 22", 2022

Albrecht Durer Gathers no Moss, 20" x 30", 2022

Dupuytren's and the Demise of Patriarchy, 30" x 22", 2022

The Sleep of Unreason, 22 1/4" x 15", 2021

If You're Hurtling Down to Lisboa, 30" x 22 1/2", 2021

Thus We Always See the Same Face, 32" x 40", 2020

Annunciation Double Header, 25" x 30", 2020

Bear or Beaver, 66" x 30", 2019

Stenographer's Daughter, 30" x 22", 2018